Ski guides don’t usually talk about getting caught in an avalanche. After all, their livelihood depends on managing clients through avalanche terrain, travelling safely, and avoiding avalanche incidents. Most simply brush it off but never forget about it. Well, I intend to change that. The reality is that we make heavy use of our beautiful, but dangerous backcountry terrain. Given our increased exposure to the hazards at play, we’re more likely to get caught in an avalanche than, say, the typical weekend warrior, even if both parties have a sound judgement and follow best practices when it comes to avalanche safety. As for me, it involves a little more than that. I’ve made some pretty critical mistakes during my training as an aspirant ski guide (and will make many more as I prepare for my final practical assessment next winter). Those mistakes sometimes led to close calls with fast-moving snow and, twice, led to me being caught off guard in potentially fatal situations. I’ve detailed below my first incident with an avalanche where I was almost fully buried and the events leading up to it so that you can learn from my mistakes.

The year was 2021. November was as stormy as it came. We had previously booked the Asulkan Hut in Rogers Pass, Glacier National Park for 3 nights/4 days. For the first three days, the storm unleashed all of its might on our cozy alpine hut. Our options were limited, to say the least. We could only safely ski the Tree Triangle below the hut, a series of quality gullies and treed slopes below the moraine on which the hut was built.

We were cautious. The strong winds and heavy precipitation (over 60cm of snow) would heighten the avalanche hazard significantly. Surprisingly, we didn’t see signs of instability, the red flags of avalanche safety consisting of surface cracking, whumpfing or natural avalanches. With a little more experience, I now know that early-season storms in the BC Interior tend to come with extremely light, dry snow which tends to form slabs with very little cohesion. Either way, it was best to remain cautious and evaluate the storm’s progression and how it was affecting the thin early season snowpack.

Related: The Early Season Snowpack: How It Affects Your Winter

By the third night, the storm had finally passed. The winds ground to a halt and the clouds parted to reveal a full moon. Woah, what a beauty! We immediately jumped back in our sweaty ski touring gear and ascended the wind-stripped alpine moraines above the Asulkan Hut, granting us a panoramic view of the Asulkan and Youngs Glaciers.

The next day, things went sideways. The skies opened up, rewarding us with a glorious, bluebird powder day. Renaud and I decided to split off from the main group and head into the glaciated slopes below Youngs Peak to ski the 7 Steps of Paradise. We made the #1 mistake taught in avalanche safety courses – beware of bluebird days right after a major storm. The stellar ski conditions are bound to hide some potentially fatal instabilities. As an ambitious human, those bouts of good weather are where I’ll naturally try to push the envelope.

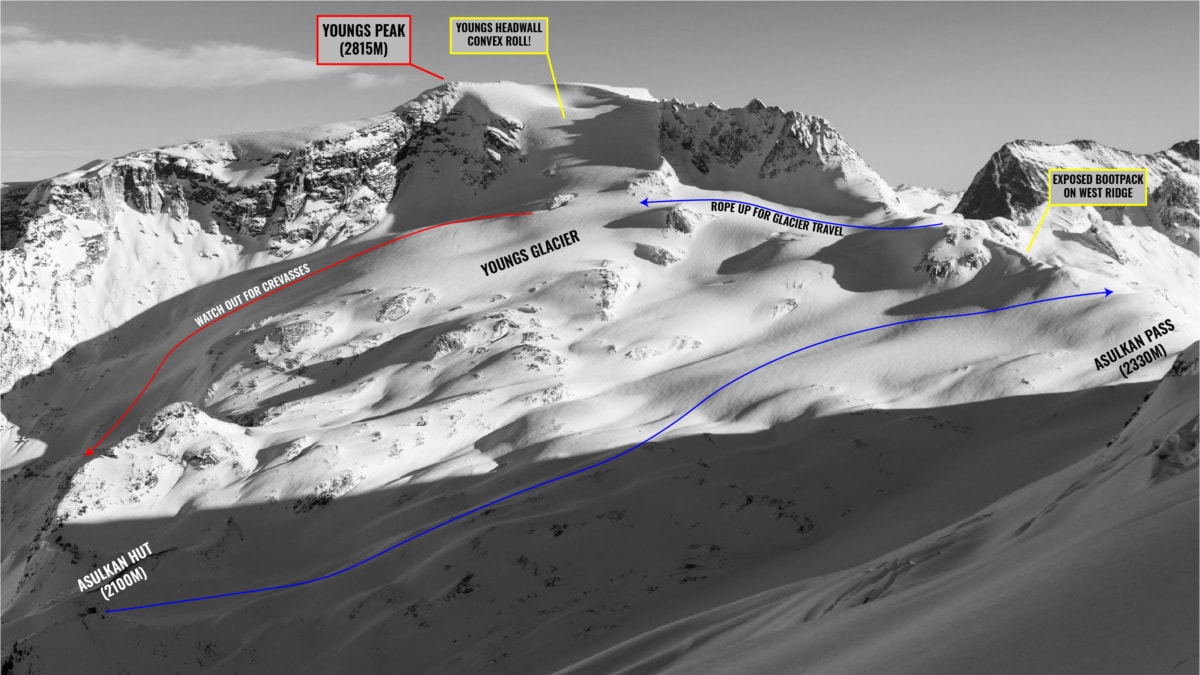

With grand excitement, we raced up the moraines above the Asulkan Hut and gained the Youngs West Ridge. From there, we booted up the rocky crest until we reached the furthest extent of the upper Youngs Glacier. The views of the Dawson Range across the Iccomapleux Valley to the South were jaw-dropping. We clipped onto our thin rope as we approached the heavily crevassed glacier. A wise choice since crevasses aren’t strongly bridged in late November.

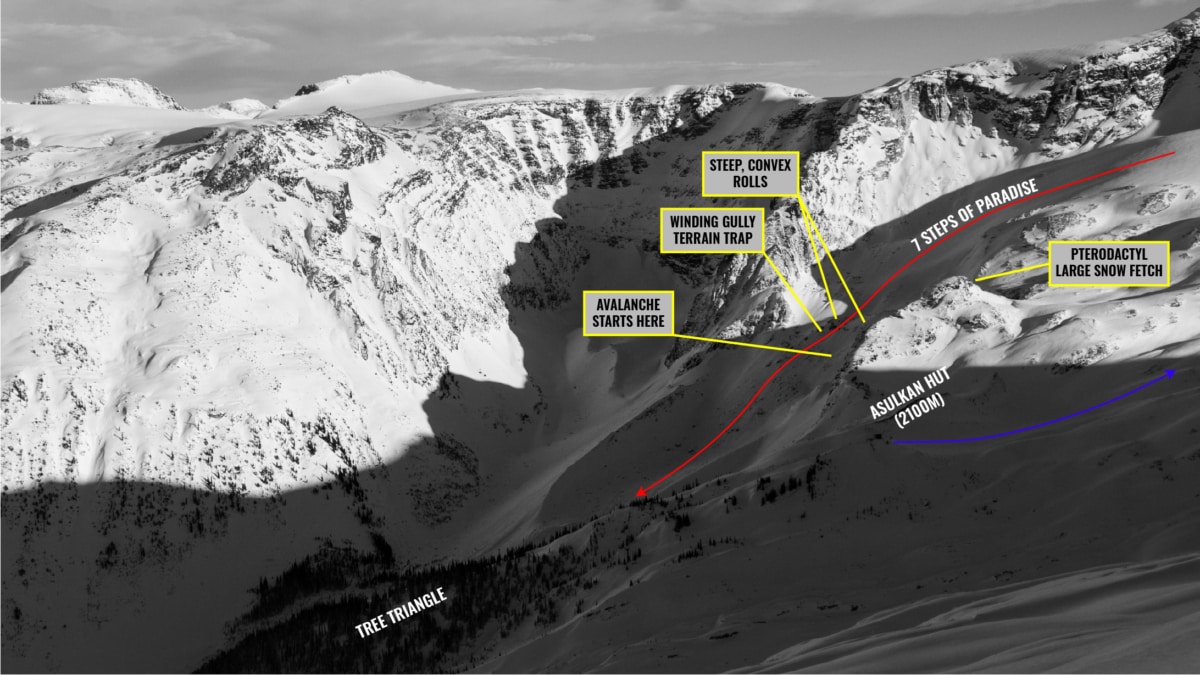

We eventually stumbled across the Youngs Headwall, a steep NW-facing glaciated slope. We stopped short of the headwall given the recent storm and the potential for storm/wind slabs at the top of the vast, convex slope. From there, we skied down the 7 Steps of Paradise, a series of rolls leading into a broad valley below the Asulkan Hut and into which the Forever Young Couloir exits. Generally speaking, we were heading for the skier’s right of the Pterodactyl, a large rock tower separating the Asulkan Hut from the Youngs Glacier. We didn’t observe any avalanche red flags during most of the descent.

Now onto the last “step” by the Pterodactyl. I lead the pitch through a winding gully flanked by large convexities on either side. The rolls were obviously wind-scoured and harbouring razor-sharp rocks. My spidey senses were tingling – we should not have been here. Still, we were determined to pursue the line. Just below the gully’s mouth, I triggered two small storm slabs, adjacent to each other. The writing was on the wall: get out! Under a panic, I kept skiing, veering left out of the gully into a vast alpine slope. I thought this would put me further away from the shooting gallery happening in the gully. To my surprise, I unwittingly traversed underneath one of the large rolls. I saw a crack shoot out from the tip of my skis and propagate across the slope. Uh oh! My avalanche training kicked in. I skied diagonally across the slope at Mach 1 and covered my mouth with my elbow holding on to my pack strap. I truly believed I could escape the moving snow by reaching its left flank.

Moments later, I was caught in the avalanche and launched forward. I was riding in a washing machine, endlessly tumbling down the slope, and pummeled by dense snow. My poles were torn off my hands, I was ejected from my skis. I couldn’t tell up from down. After what seemed like an eternity, I ground to a halt. While I was immobilized, the snow started covering my head. The weight was unbearable like being cast in concrete. The faint glimmer of light was replaced with darkness. I panicked. I couldn’t breathe: my throat was filled with snow despite my best efforts. I prayed Renaud would find me with his avalanche transceiver. Fortunately, I wasn’t a lost cause yet. I freed my right arm and dug a narrow breathing hole. I took the most painful breath, inhaling icy snow. I was buried face down with my upper body sideways and my legs straight down as if I was bending over. My head must have been covered by no more than 10cm of snow at most. Lucky me! With hard work, I managed to escape from my frigid prison cell by the time Renaud skied down to me. Looking up, the avalanche crown varied from 10 to 60cm and spanned 70-100m across the convex roll. The slope angle was roughly 30-35 degrees, prime avalanche terrain in other words.

After the incident, I analyzed the events and figured out my mistakes that led to getting caught in an avalanche:

- Going out in consequential alpine terrain after a major storm was a bold choice. Best to stick to conservative terrain while the snow settles out.

- The convex roll is located right below a trough leading up to Youngs Glacier. Katabatic winds race down the glacier and funnel through the trough blowing large amounts of snow over the roll onto its lee side of the roll. I essentially traversed under a storm/wind slab factory!

- Snow is blown from the adjacent Pterodactyl and deposited on the slope, which accelerates slab development.

- The avalanche ran on a smooth melt-freeze crust which offered a polished bed surface further weakening the slab’s bond with the underlying snowpack layers.

- We were both caught off guard after seeing no evidence of snowpack instability prior to the avalanche. We should have instead remained conservative even if our observations didn’t line up with the previous storm.

By Rogers Pass standards, this avalanche was by no means a “huge” one: a size 2 to 2.5 in terms of destructive potential. That’s when I realized it doesn’t take much to bury a person. Add some hazardous terrain traps, and you’ve got the recipe for a disaster. The incident was a valuable wake-up call to the point where I’ve been much more conservative in my avalanche decision-making since then. I genuinely hope you can learn from my mistakes and avoid getting caught in an avalanche!

A BREATH TAKING STORY THAT LUCKILY DID NOT END IN TRAGEDY. A REMINDER THAT DISCRESSION IS THE BETTER PART OF VALOUR. IN MY PERSONAL PERILS IN THE WESTERN CORDILLERA, CLOSE CALLS BEGAN WITH CURIOSITY, DARING AND STUPIDITY.

Agreed. Best to stay humble when travelling in the mountains!